What’s the point of ‘Audiophile’ recordings (and what can they tell you about yourself)?

By Roy Gregory

Audiophile record labels have been part of the high-end scene for almost as long as the high-end scene has existed. It stands to reason – if people are prepared to pay more for more performance from their audio systems, then they’ll also be prepared to pay more for ‘better’ recordings. Perhaps the best-known exponents of the approach are Sheffield Labs and Reference Recordings, but plenty of others have existed, from M&K Realtime and Water Lily to Wilson Audio (who started life as a record label).

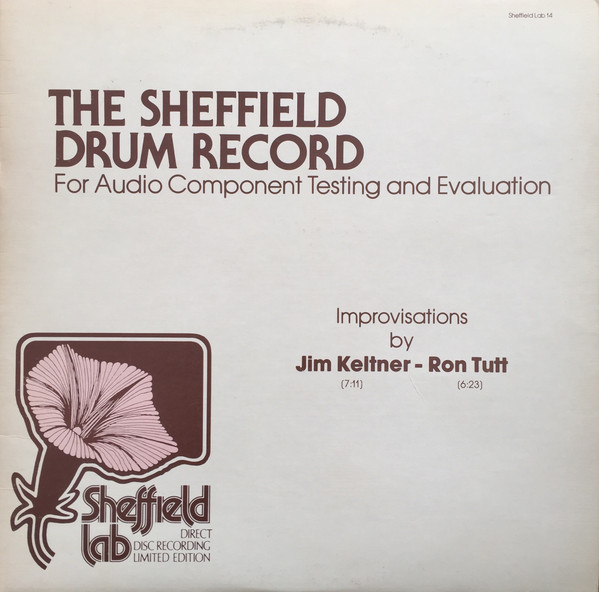

It wasn’t long before titles like For Duke and Dafos, the Sheffield Drum and Track records or James Newton Howerd & Friends become core demonstration material, for manufacturers at shows and dealers in customer demos. In fact, it’s surprising how often you still hear these discs at shows or manufacturer’s presentations even today. In fact, the first LP I heard played on the Wilson WAMM MCS was none other than For Duke… Okay, so I’ll admit that every one of those LPs is in my collection. But – and here’s the rub – I really can’t remember the last time I played any of them! These are not records and not music that I pull out to enjoy. In fact, given how few audiophile recordings possess even modest musical merit, it’s hard to escape the conclusion that they exist mainly to show off the systems they’re played on.

And that in a nutshell, is the challenge facing any audiophile label. In a world where a great performance can transcend a poor recording, the reality facing audiophile labels (and their essential flaw) is and always has been, the quality of the musicians they record rather than the quality of the recordings per se. Musically speaking, the performer and performance is everything. When transcribed 78s or re-purposed live radio broadcasts by stellar musicians (think Armstrong, Heifetz, Wicks or Martzy to name just a few) can be used as the source for thrilling and compelling records and CDs, why waste time on pristine recordings of the local school choir? Okay, so I’m exaggerating, but actually, not by much…

And that in a nutshell, is the challenge facing any audiophile label. In a world where a great performance can transcend a poor recording, the reality facing audiophile labels (and their essential flaw) is and always has been, the quality of the musicians they record rather than the quality of the recordings per se. Musically speaking, the performer and performance is everything. When transcribed 78s or re-purposed live radio broadcasts by stellar musicians (think Armstrong, Heifetz, Wicks or Martzy to name just a few) can be used as the source for thrilling and compelling records and CDs, why waste time on pristine recordings of the local school choir? Okay, so I’m exaggerating, but actually, not by much…

There are a (very) few exceptions to this ‘great recording of a musical desert’ rule. I have a personal soft-spot for a few of the Reference Recordings discs. Their LPs of both the Keith Clark/Pacific S.O. Appalachian Spring (R-22) and Menotti/Barber Violin Concertos (RR-45) as well as the Dallas Wind’s recording of Holst’s Wind Suites (under the Hammersmith title, RR-39) are records that I regularly return to – the former for its sheer life and vitality, the latter as the sole reading of these rather beautiful works in my collection. But like I said, these really are the exceptions. I might occasionally drag out Testament (RR-49) or the Rutter Requiem (RR-57) when I want a really good recording of a massed choir, but even in this case, there are always alternatives.

Happy accidents?

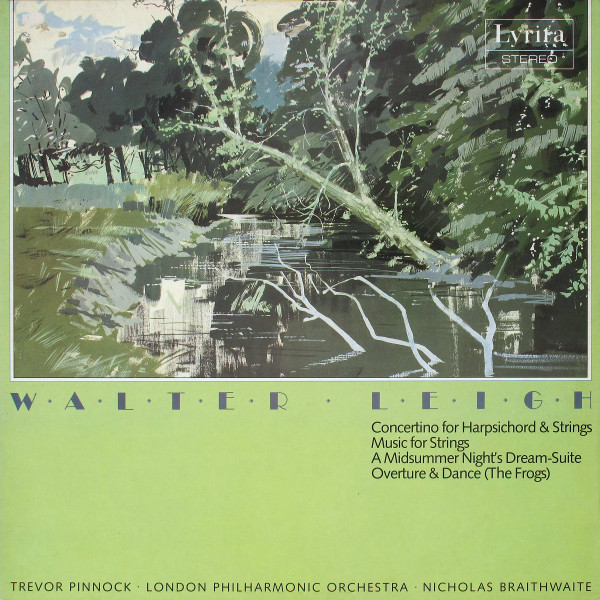

As an aside, there are a number of labels (Lyrita and SayDisc/Amon Ra are obvious examples) that specialised in unusual or off-beat repertoire. Lyrita managed to create a comprehensive catalogue of material from British composers that had remained firmly under the radar of mainstream popularity. Although they did record works by Elgar, Holst and Bax, the likes of Bantock, Rubbra, Maconchy, Ireland and Harrison Birtwistle were more their bread and butter. In a similar vein, SayDisc concentrated on early music (especially folksongs) or Asian, African or Arabic music, often played on simple or unfamiliar instruments, long before any of these were fashionable. But what both labels did was combine eclectic (often unique) musical content with genuinely excellent recordings – although such labels are more market aberrations than deliberate attempts to appeal to the audiophile buyer.